Functions are one of the fundamental building blocks in JavaScript. A function is a JavaScript procedure-a set of statements that performs a task or calculates a value. To use a function, you must define it somewhere in the scope from which you wish to call it.

A method is a function that is a property of an object. Read more about objects and methods in Working with objects .

Calling functionsDefining a function does not execute it. Defining the function simply names the function and specifies what to do when the function is called. Calling the function actually performs the specified actions with the indicated parameters. For example, if you define the function square , you could call it as follows:

Square(5);

The preceding statement calls the function with an argument of 5. The function executes its statements and returns the value 25.

Functions must be in scope when they are called, but the function declaration can be hoisted (appear below the call in the code), as in this example:

Console.log(square(5)); /* ... */ function square(n) { return n * n; }

The scope of a function is the function in which it is declared, or the entire program if it is declared at the top level.

Note: This works only when defining the function using the above syntax (i.e. function funcName(){}). The code below will not work. That means, function hoisting only works with function declaration and not with function expression.

Console.log(square); // square is hoisted with an initial value undefined. console.log(square(5)); // TypeError: square is not a function var square = function(n) { return n * n; }

The arguments of a function are not limited to strings and numbers. You can pass whole objects to a function. The show_props() function (defined in ) is an example of a function that takes an object as an argument.

A function can call itself. For example, here is a function that computes factorials recursively:

Function factorial(n) { if ((n === 0) || (n === 1)) return 1; else return (n * factorial(n - 1)); }

You could then compute the factorials of one through five as follows:

Var a, b, c, d, e; a = factorial(1); // a gets the value 1 b = factorial(2); // b gets the value 2 c = factorial(3); // c gets the value 6 d = factorial(4); // d gets the value 24 e = factorial(5); // e gets the value 120

There are other ways to call functions. There are often cases where a function needs to be called dynamically, or the number of arguments to a function vary, or in which the context of the function call needs to be set to a specific object determined at runtime. It turns out that functions are, themselves, objects, and these objects in turn have methods (see the Function object). One of these, the apply() method, can be used to achieve this goal.

Function scopeVariables defined inside a function cannot be accessed from anywhere outside the function, because the variable is defined only in the scope of the function. However, a function can access all variables and functions defined inside the scope in which it is defined. In other words, a function defined in the global scope can access all variables defined in the global scope. A function defined inside another function can also access all variables defined in its parent function and any other variable to which the parent function has access.

// The following variables are defined in the global scope var num1 = 20, num2 = 3, name = "Chamahk"; // This function is defined in the global scope function multiply() { return num1 * num2; } multiply(); // Returns 60 // A nested function example function getScore() { var num1 = 2, num2 = 3; function add() { return name + " scored " + (num1 + num2); } return add(); } getScore(); // Returns "Chamahk scored 5"

Scope and the function stack RecursionA function can refer to and call itself. There are three ways for a function to refer to itself:

For example, consider the following function definition:

Var foo = function bar() { // statements go here };

Within the function body, the following are all equivalent:

A function that calls itself is called a recursive function . In some ways, recursion is analogous to a loop. Both execute the same code multiple times, and both require a condition (to avoid an infinite loop, or rather, infinite recursion in this case). For example, the following loop:

Var x = 0; while (x < 10) { // "x < 10" is the loop condition // do stuff x++; }

can be converted into a recursive function and a call to that function:

Function loop(x) { if (x >= 10) // "x >= 10" is the exit condition (equivalent to "!(x < 10)") return; // do stuff loop(x + 1); // the recursive call } loop(0);

However, some algorithms cannot be simple iterative loops. For example, getting all the nodes of a tree structure (e.g. the DOM) is more easily done using recursion:

Function walkTree(node) { if (node == null) // return; // do something with node for (var i = 0; i < node.childNodes.length; i++) { walkTree(node.childNodes[i]); } }

Compared to the function loop , each recursive call itself makes many recursive calls here.

It is possible to convert any recursive algorithm to a non-recursive one, but often the logic is much more complex and doing so requires the use of a stack. In fact, recursion itself uses a stack: the function stack.

The stack-like behavior can be seen in the following example:

Function foo(i) { if (i < 0) return; console.log("begin: " + i); foo(i - 1); console.log("end: " + i); } foo(3); // Output: // begin: 3 // begin: 2 // begin: 1 // begin: 0 // end: 0 // end: 1 // end: 2 // end: 3

Nested functions and closuresYou can nest a function within a function. The nested (inner) function is private to its containing (outer) function. It also forms a closure . A closure is an expression (typically a function) that can have free variables together with an environment that binds those variables (that "closes" the expression).

Since a nested function is a closure, this means that a nested function can "inherit" the arguments and variables of its containing function. In other words, the inner function contains the scope of the outer function.

- The inner function can be accessed only from statements in the outer function.

- The inner function forms a closure: the inner function can use the arguments and variables of the outer function, while the outer function cannot use the arguments and variables of the inner function.

The following example shows nested functions:

Function addSquares(a, b) { function square(x) { return x * x; } return square(a) + square(b); } a = addSquares(2, 3); // returns 13 b = addSquares(3, 4); // returns 25 c = addSquares(4, 5); // returns 41

Since the inner function forms a closure, you can call the outer function and specify arguments for both the outer and inner function:

Function outside(x) { function inside(y) { return x + y; } return inside; } fn_inside = outside(3); // Think of it like: give me a function that adds 3 to whatever you give // it result = fn_inside(5); // returns 8 result1 = outside(3)(5); // returns 8

Preservation of variablesNotice how x is preserved when inside is returned. A closure must preserve the arguments and variables in all scopes it references. Since each call provides potentially different arguments, a new closure is created for each call to outside. The memory can be freed only when the returned inside is no longer accessible.

This is not different from storing references in other objects, but is often less obvious because one does not set the references directly and cannot inspect them.

Multiply-nested functionsFunctions can be multiply-nested, i.e. a function (A) containing a function (B) containing a function (C). Both functions B and C form closures here, so B can access A and C can access B. In addition, since C can access B which can access A, C can also access A. Thus, the closures can contain multiple scopes; they recursively contain the scope of the functions containing it. This is called scope chaining . (Why it is called "chaining" will be explained later.)

Consider the following example:

Function A(x) { function B(y) { function C(z) { console.log(x + y + z); } C(3); } B(2); } A(1); // logs 6 (1 + 2 + 3)

In this example, C accesses B "s y and A "s x . This can be done because:

The reverse, however, is not true. A cannot access C , because A cannot access any argument or variable of B , which C is a variable of. Thus, C remains private to only B .

Name conflictsWhen two arguments or variables in the scopes of a closure have the same name, there is a name conflict . More inner scopes take precedence, so the inner-most scope takes the highest precedence, while the outer-most scope takes the lowest. This is the scope chain. The first on the chain is the inner-most scope, and the last is the outer-most scope. Consider the following:

Function outside() { var x = 5; function inside(x) { return x * 2; } return inside; } outside()(10); // returns 20 instead of 10

The name conflict happens at the statement return x and is between inside "s parameter x and outside "s variable x . The scope chain here is { inside , outside , global object}. Therefore inside "s x takes precedences over outside "s x , and 20 (inside "s x) is returned instead of 10 (outside "s x).

ClosuresClosures are one of the most powerful features of JavaScript. JavaScript allows for the nesting of functions and grants the inner function full access to all the variables and functions defined inside the outer function (and all other variables and functions that the outer function has access to). However, the outer function does not have access to the variables and functions defined inside the inner function. This provides a sort of encapsulation for the variables of the inner function. Also, since the inner function has access to the scope of the outer function, the variables and functions defined in the outer function will live longer than the duration of the outer function execution, if the inner function manages to survive beyond the life of the outer function. A closure is created when the inner function is somehow made available to any scope outside the outer function.

Var pet = function(name) { // The outer function defines a variable called "name" var getName = function() { return name; // The inner function has access to the "name" variable of the outer //function } return getName; // Return the inner function, thereby exposing it to outer scopes } myPet = pet("Vivie"); myPet(); // Returns "Vivie"

It can be much more complex than the code above. An object containing methods for manipulating the inner variables of the outer function can be returned.

Var createPet = function(name) { var sex; return { setName: function(newName) { name = newName; }, getName: function() { return name; }, getSex: function() { return sex; }, setSex: function(newSex) { if(typeof newSex === "string" && (newSex.toLowerCase() === "male" || newSex.toLowerCase() === "female")) { sex = newSex; } } } } var pet = createPet("Vivie"); pet.getName(); // Vivie pet.setName("Oliver"); pet.setSex("male"); pet.getSex(); // male pet.getName(); // Oliver

In the code above, the name variable of the outer function is accessible to the inner functions, and there is no other way to access the inner variables except through the inner functions. The inner variables of the inner functions act as safe stores for the outer arguments and variables. They hold "persistent" and "encapsulated" data for the inner functions to work with. The functions do not even have to be assigned to a variable, or have a name.

Var getCode = (function() { var apiCode = "0]Eal(eh&2"; // A code we do not want outsiders to be able to modify... return function() { return apiCode; }; })(); getCode(); // Returns the apiCode

There are, however, a number of pitfalls to watch out for when using closures. If an enclosed function defines a variable with the same name as the name of a variable in the outer scope, there is no way to refer to the variable in the outer scope again.

Var createPet = function(name) { // The outer function defines a variable called "name". return { setName: function(name) { // The enclosed function also defines a variable called "name". name = name; // How do we access the "name" defined by the outer function? } } }

Using the arguments objectThe arguments of a function are maintained in an array-like object. Within a function, you can address the arguments passed to it as follows:

Arguments[i]

where i is the ordinal number of the argument, starting at zero. So, the first argument passed to a function would be arguments . The total number of arguments is indicated by arguments.length .

Using the arguments object, you can call a function with more arguments than it is formally declared to accept. This is often useful if you don"t know in advance how many arguments will be passed to the function. You can use arguments.length to determine the number of arguments actually passed to the function, and then access each argument using the arguments object.

For example, consider a function that concatenates several strings. The only formal argument for the function is a string that specifies the characters that separate the items to concatenate. The function is defined as follows:

Function myConcat(separator) { var result = ""; // initialize list var i; // iterate through arguments for (i = 1; i < arguments.length; i++) { result += arguments[i] + separator; } return result; }

You can pass any number of arguments to this function, and it concatenates each argument into a string "list":

// returns "red, orange, blue, " myConcat(", ", "red", "orange", "blue"); // returns "elephant; giraffe; lion; cheetah; " myConcat("; ", "elephant", "giraffe", "lion", "cheetah"); // returns "sage. basil. oregano. pepper. parsley. " myConcat(". ", "sage", "basil", "oregano", "pepper", "parsley");

Note: The arguments variable is "array-like", but not an array. It is array-like in that it has a numbered index and a length property. However, it does not possess all of the array-manipulation methods.

Two factors influenced the introduction of arrow functions: shorter functions and non-binding of this .

Shorter functionsIn some functional patterns, shorter functions are welcome. Compare:

Var a = [ "Hydrogen", "Helium", "Lithium", "Beryllium" ]; var a2 = a.map(function(s) { return s.length; }); console.log(a2); // logs var a3 = a.map(s => s.length); console.log(a3); // logs

No separate thisUntil arrow functions, every new function defined its own value (a new object in the case of a constructor, undefined in function calls, the base object if the function is called as an "object method", etc.). This proved to be less than ideal with an object-oriented style of programming.

Function Person() { // The Person() constructor defines `this` as itself. this.age = 0; setInterval(function growUp() { // In nonstrict mode, the growUp() function defines `this` // as the global object, which is different from the `this` // defined by the Person() constructor. this.age++; }, 1000); } var p = new Person();

In ECMAScript 3/5, this issue was fixed by assigning the value in this to a variable that could be closed over.

Function Person() { var self = this; // Some choose `that` instead of `self`. // Choose one and be consistent. self.age = 0; setInterval(function growUp() { // The callback refers to the `self` variable of which // the value is the expected object. self.age++; }, 1000); }

JavaScript function позволяют организовать скрипты и упрощают повторное использование кода. Вместо того чтобы создавать длинные фрагменты кода, разбросанные по всей HTML-странице , скрипты организуются в логические группы.

Объявление и вызов функции JavaScriptСинтаксис функции JavaScript выглядит следующим образом:

function ""имя"" (""аргумент1"", ""аргумент2"", ""аргумент3"" ...) { ""операторы"" return ""значение"" }

Имя определяет, как мы будем называть функцию при ее вызове. Аргументы задают значения, которые передаются функции для обработки. Раздел операторы представляет собой тело функции, которая выполняет обработку. Необязательный оператор return позволяет вернуть значение.

В следующем примере показана функция, определяемая в разделе HTML-страницы и вызываемая в разделе :

function sayHello() { alert("Привет!"); } sayHello();

Передача аргументов в функциюВ приведенном выше примере (script type text JavaScript function ) функции не передается никакие аргументы. Обычно функция предназначена для выполнения каких-либо действий с несколькими аргументами:

Простой пример функции JavaScript function sayHello(day, month) { alert("Привет! Сегодня " + day + " " + month); } sayHello("24", "Июля"); sayHello ("1", "Августа"); sayHello ("24", "Мая");

В этом примере JavaScript callback function вызывается несколько раз, принимая аргументы, которые затем используются для создания строки, отображаемой в диалоговом окне. Чтобы сделать это без функции, нужно было бы повторить скрипт в разделе три раза. Очевидно, что использование функции является более эффективным подходом.

Возврат значения из функцииОператор return применяется для возврата значения из функции и его использования в месте, где вызывается функция. В качестве примера мы объявим функцию, которая складывает два аргумента и возвращает результат:

Простой пример функции JavaScript var result = addValues(10, 20) document.write ("Результат = " + result);

В приведенном выше примере мы передаем в функцию addValues значения 10 и 20 . Функция addValues складывает эти два значения и возвращает результат. Оператор return присваивает результат переменной result, которая затем используется для создания строки, выводимой на HTML-странице .

Вызов JavaScript function может быть выполнен в разных местах. Например, не обязательно присваивать результат в качестве значения переменной. Можно использовать его непосредственно в качестве аргумента при вызове document.write .

Важно отметить, что функция может возвращать только одно значение:

Простой пример функции JavaScript function addValues(value1, value2) { return value1 + value2; } document.write ("Результат = " + addValues(10, 20)); JavaScript onclick function также могут использоваться в условных выражениях. Например: Простой пример функции JavaScript function addValues(value1, value2) { return value1 + value2; } if (addValues(10, 20) > 20) { document.write ("Результат > 20"); } else { document.write ("Результат < 20"); }

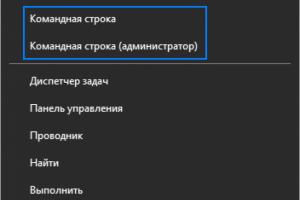

Где размещать объявления функцийЕсть два места, в которых рекомендуется размещать объявления JavaScript function return: внутри раздела HTML-документа или во внешнем файле .js . Наиболее предпочтительным местом считается второй вариант, так как он обеспечивает наибольшую гибкость.

Цель создания функций — сделать их как можно более общими для того, чтобы максимизировать возможность повторного использования.

Перевод статьи «Understanding JavaScript Functions » был подготовлен дружной командой проекта .

Хорошо Плохо

В этой статье описаны функции Javascript на уровне языка: создание, параметры, приемы работы, замыкания и многое другое.

Создание функцийСуществует 3 способа создать функцию. Основное отличие в результате их работы - в том, что именованная функция видна везде, а анонимная - только после объявления:

Функции - объектыВ javascript функции являются полноценными объектами встроенного класса Function. Именно поэтому их можно присваивать переменным, передавать и, конечно, у них есть свойства:

Function f() { ... } f.test = 6 ... alert(f.test) // 6

Свойства функции доступны и внутри функции, так что их можно использовать как статические переменные.

Например,

Function func() { var funcObj = arguments.callee funcObj.test++ alert(funcObj.test) } func.test = 1 func() func()

В начале работы каждая функция создает внутри себя переменную arguments и присваивает arguments.callee ссылку на себя. Так что arguments.callee.test - свойство func.test , т.е статическая переменная test.

В примере нельзя было сделать присвоение:

Var test = arguments.callee.test test++

так как при этом операция ++ сработала бы на локальной переменной test , а не на свойстве test объекта функции.

Объект arguments также содержит все аргументы и может быть преобразован в массив (хотя им не является), об этом - ниже, в разделе про параметры.

Области видимостиКаждая функция, точнее даже каждый запуск функции задает свою индивидуальную область видимости.

Переменные можно объявлять в любом месте. Ключевое слово var задает переменную в текущей области видимости. Если его забыть, то переменная попадет в глобальный объект window . Возможны неожиданные пересечения с другими переменными окна, конфликты и глюки.

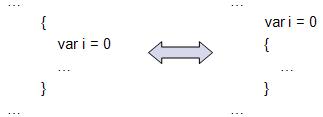

В отличие от ряда языков, блоки не задают отдельную область видимости. Без разницы - определена переменная внутри блока или вне его. Так что эти два фрагмента совершенно эквивалентны:

Заданная через var переменная видна везде в области видимости, даже до оператора var . Для примера сделаем функцию, которая будет менять переменную, var для которой находится ниже.

Например:

Function a() { z = 5 // поменяет z локально.. // .. т.к z объявлена через var var z } // тест delete z // очистим на всякий случай глобальную z a() alert(window.z) // => undefined, т.к z была изменена локально

Параметры функцииФункции можно запускать с любым числом параметров.

Если функции передано меньше параметров, чем есть в определении, то отсутствующие считаются undefined .

Следующая функция возвращает время time , необходимое на преодоление дистанции distance с равномерной скоростью speed .

При первом запуске функция работает с аргументами distance=10 , speed=undefined . Обычно такая ситуация, если она поддерживается функцией, предусматривает значение по умолчанию:

// если speed - ложное значение(undefined, 0, false...) - подставить 10 speed = speed || 10

Оператор || в яваскрипт возвращает не true/false , а само значение (первое, которое приводится к true).

Поэтому его используют для задания значений по умолчанию. В нашем вызове speed будет вычислено как undefined || 10 = 10 .

Поэтому результат будет 10/10 = 1 .

Второй запуск - стандартный.

Третий запуск задает несколько дополнительных аргументов. В функции не предусмотрена работа с дополнительными аргументами, поэтому они просто игнорируются.

Ну и в последнем случае аргументов вообще нет, поэтому distance = undefined , и имеем результат деления undefined/10 = NaN (Not-A-Number, произошла ошибка).

Работа с неопределенным числом параметровНепосредственно перед входом в тело функции, автоматически создается объект arguments , который содержит

Например,

Function func() { for(var i=0;i alert(3)

Пример передачи функции по ссылкеФункцию легко можно передавать в качестве аргумента другой функции.

Например, map берет функцию func , применяет ее к каждому элементу массива arr и возвращает получившийся массив:

Var map = function(func, arr) { var result = for(var i=0; i target) return null; else return find(start + 5, "(" + history + " + 5)") || find(start * 3, "(" + history + " * 3)"); } return find(1, "1"); } console.log(findSolution(24)); // → (((1 * 3) + 5) * 3)

Этот пример не обязательно находит самое короткое решение – он удовлетворяется любым. Не ожидаю, что вы сразу поймёте, как программа работает. Но давайте разбираться в этом отличном упражнении на рекурсивное мышление.

Внутренняя функция find занимается рекурсией. Она принимает два аргумента – текущее число и строку, которая содержит запись того, как мы пришли к этому номеру. И возвращает либо строчку, показывающую нашу последовательность шагов, либо null.

Для этого функция выполняет одно из трёх действий. Если заданное число равно цели, то текущая история как раз и является способом её достижения, поэтому она и возвращается. Если заданное число больше цели, продолжать умножения и сложения смысла нет, потому что так оно будет только увеличиваться. А если мы ещё не достигли цели, функция пробует оба возможных пути, начинающихся с заданного числа. Она дважды вызывает себя, один раз с каждым из способов. Если первый вызов возвращает не null, он возвращается. В другом случае возвращается второй.

Чтобы лучше понять, как функция достигает нужного эффекта, давайте просмотрим её вызовы, которые происходят в поисках решения для числа 13.

Find(1, "1") find(6, "(1 + 5)") find(11, "((1 + 5) + 5)") find(16, "(((1 + 5) + 5) + 5)") too big find(33, "(((1 + 5) + 5) * 3)") too big find(18, "((1 + 5) * 3)") too big find(3, "(1 * 3)") find(8, "((1 * 3) + 5)") find(13, "(((1 * 3) + 5) + 5)") found!

Отступ показывает глубину стека вызовов. В первый раз функция find вызывает сама себя дважды, чтобы проверить решения, начинающиеся с (1 + 5) и (1 * 3). Первый вызов ищет решение, начинающееся с (1 + 5), и при помощи рекурсии проверяет все решения, выдающие число, меньшее или равное требуемому. Не находит, и возвращает null. Тогда-то оператор || и переходит к вызову функции, который исследует вариант (1 * 3). Здесь нас ждёт удача, потому что в третьем рекурсивном вызове мы получаем 13. Этот вызов возвращает строку, и каждый из операторов || по пути передаёт эту строку выше, в результате возвращая решение.

Выращиваем функции Существует два более-менее естественных способа ввода функций в программу.Первый – вы пишете схожий код несколько раз. Этого нужно избегать – больше кода означает больше места для ошибок и больше материала для чтения тех, кто пытается понять программу. Так что мы берём повторяющуюся функциональность, подбираем ей хорошее имя и помещаем её в функцию.

Второй способ – вы обнаруживаете потребность в некоей новой функциональности, которая достойна помещения в отдельную функцию. Вы начинаете с названия функции, и затем пишете её тело. Можно даже начинать с написания кода, использующего функцию, до того, как сама функция будет определена.

То, насколько сложно вам подобрать имя для функции, показывает, как хорошо вы представляете себе её функциональность. Возьмём пример. Нам нужно написать программу, выводящую два числа, количество коров и куриц на ферме, за которыми идут слова «коров» и «куриц». К числам нужно спереди добавить нули так, чтобы каждое занимало ровно три позиции.

007 Коров 011 Куриц

Очевидно, что нам понадобится функция с двумя аргументами. Начинаем кодить.

// вывестиИнвентаризациюФермы

function printFarmInventory(cows, chickens) {

var cowString = String(cows);

while (cowString.length < 3)

cowString = "0" + cowString;

console.log(cowString + " Коров");

var chickenString = String(chickens);

while (chickenString.length < 3)

chickenString = "0" + chickenString;

console.log(chickenString + " Куриц");

}

printFarmInventory(7, 11);

Если мы добавим к строке.length, мы получим её длину. Получается, что циклы while добавляют нули спереди к числам, пока не получат строчку в 3 символа.

Готово! Но только мы собрались отправить фермеру код (вместе с изрядным чеком, разумеется), он звонит и говорит нам, что у него в хозяйстве появились свиньи, и не могли бы мы добавить в программу вывод количества свиней?

Можно, конечно. Но когда мы начинаем копировать и вставлять код из этих четырёх строчек, мы понимаем, что надо остановиться и подумать. Должен быть способ лучше. Пытаемся улучшить программу:

// выводСДобавлениемНулейИМеткой function printZeroPaddedWithLabel(number, label) { var numberString = String(number); while (numberString.length < 3) numberString = "0" + numberString; console.log(numberString + " " + label); } // вывестиИнвентаризациюФермы function printFarmInventory(cows, chickens, pigs) { printZeroPaddedWithLabel(cows, "Коров"); printZeroPaddedWithLabel(chickens, "Куриц"); printZeroPaddedWithLabel(pigs, "Свиней"); } printFarmInventory(7, 11, 3);

Работает! Но название printZeroPaddedWithLabel немного странное. Оно объединяет три вещи – вывод, добавление нулей и метку – в одну функцию. Вместо того, чтобы вставлять в функцию весь повторяющийся фрагмент, давайте выделим одну концепцию:

// добавитьНулей function zeroPad(number, width) { var string = String(number); while (string.length < width) string = "0" + string; return string; } // вывестиИнвентаризациюФермы function printFarmInventory(cows, chickens, pigs) { console.log(zeroPad(cows, 3) + " Коров"); console.log(zeroPad(chickens, 3) + " Куриц"); console.log(zeroPad(pigs, 3) + " Свиней"); } printFarmInventory(7, 16, 3);

Функция с хорошим, понятным именем zeroPad облегчает понимание кода. И её можно использовать во многих ситуациях, не только в нашем случае. К примеру, для вывода отформатированных таблиц с числами.

Насколько умными и универсальными должны быть функции? Мы можем написать как простейшую функцию, которая дополняет число нулями до трёх позиций, так и навороченную функцию общего назначения для форматирования номеров, поддерживающую дроби, отрицательные числа, выравнивание по точкам, дополнение разными символами, и т.п.

Хорошее правило – добавляйте только ту функциональность, которая вам точно пригодится. Иногда появляется искушение создавать фреймворки общего назначения для каждой небольшой потребности. Сопротивляйтесь ему. Вы никогда не закончите работу, а просто напишете кучу кода, который никто не будет использовать.

Функции и побочные эффекты Функции можно грубо разделить на те, что вызываются из-за своих побочных эффектов, и те, что вызываются для получения некоторого значения. Конечно, возможно и объединение этих свойств в одной функции.Первая вспомогательная функция в примере с фермой, printZeroPaddedWithLabel, вызывается из-за побочного эффекта: она выводит строку. Вторая, zeroPad, из-за возвращаемого значения. И это не совпадение, что вторая функция пригождается чаще первой. Функции, возвращающие значения, легче комбинировать друг с другом, чем функции, создающие побочные эффекты.

Чистая функция – особый вид функции, возвращающей значения, которая не только не имеет побочных эффектов, но и не зависит от побочных эффектов остального кода – к примеру, не работает с глобальными переменными, которые могут быть случайно изменены где-то ещё. Чистая функция, будучи вызванной с одними и теми же аргументами, возвращает один и тот же результат (и больше ничего не делает) – что довольно приятно. С ней просто работать. Вызов такой функции можно мысленно заменять результатом её работы, без изменения смысла кода. Когда вы хотите проверить такую функцию, вы можете просто вызвать её, и быть уверенным, что если она работает в данном контексте, она будет работать в любом. Не такие чистые функции могут возвращать разные результаты в зависимости от многих факторов, и иметь побочные эффекты, которые сложно проверять и учитывать.

Однако, не надо стесняться писать не совсем чистые функции, или начинать священную чистку кода от таких функций. Побочные эффекты часто полезны. Нет способа написать чистую версию функции console.log, и эта функция весьма полезна. Некоторые операции легче выразить, используя побочные эффекты.

Итог Эта глава показала вам, как писать собственные функции. Когда ключевое слово function используется в виде выражения, возвращает указатель на вызов функции. Когда оно используется как инструкция, вы можете объявлять переменную, назначая ей вызов функции.Ключевой момент в понимании функций – локальные области видимости. Параметры и переменные, объявленные внутри функции, локальны для неё, пересоздаются каждый раз при её вызове, и не видны снаружи. Функции, объявленные внутри другой функции, имеют доступ к её области видимости.

Очень полезно разделять разные задачи, выполняемые программой, на функции. Вам не придётся повторяться, функции делают код более читаемым, разделяя его на смысловые части, так же, как главы и секции книги помогают в организации обычного текста.

УпражненияМинимум В предыдущей главе была упомянута функция Math.min, возвращающая самый маленький из аргументов. Теперь мы можем написать такую функцию сами. Напишите функцию min, принимающую два аргумента, и возвращающую минимальный из них.Console.log(min(0, 10)); // → 0 console.log(min(0, -10)); // → -10

Рекурсия Мы видели, что оператор % (остаток от деления) может использоваться для определения того, чётное ли число (% 2). А вот ещё один способ определения:Ноль чётный.

Единица нечётная.

У любого числа N чётность такая же, как у N-2.

Напишите рекурсивную функцию isEven согласно этим правилам. Она должна принимать число и возвращать булевское значение.

Потестируйте её на 50 и 75. Попробуйте задать ей -1. Почему она ведёт себя таким образом? Можно ли её как-то исправить?

Test it on 50 and 75. See how it behaves on -1. Why? Can you think of a way to fix this?

Console.log(isEven(50)); // → true console.log(isEven(75)); // → false console.log(isEven(-1)); // → ??

Считаем бобы.Символ номер N строки можно получить, добавив к ней.charAt(N) (“строчка”.charAt(5)) – схожим образом с получением длины строки при помощи.length. Возвращаемое значение будет строковым, состоящим из одного символа (к примеру, “к”). У первого символа строки позиция 0, что означает, что у последнего символа позиция будет string.length – 1. Другими словами, у строки из двух символов длина 2, а позиции её символов будут 0 и 1.

Напишите функцию countBs, которая принимает строку в качестве аргумента, и возвращает количество символов “B”, содержащихся в строке.

Затем напишите функцию countChar, которая работает примерно как countBs, только принимает второй параметр - символ, который мы будем искать в строке (вместо того, чтобы просто считать количество символов “B”). Для этого переделайте функцию countBs.